THE VISIBLE HAND: The Managerial Revolution In American Business – Alfred D. Chandler, 1977

Alfred D. Chandler’s book, written in 1977, was an attempt to fill what he considered a “void” in studies on the history of the rise of the modern business class, and to examine the changing processes of production and distribution in the U.S. as a result of the business enterprises that developed during the 19thCentury. As he writes, some pre-1930s scholars had “begrudgingly accepted [the] existence” of the modern business enterprise; mostly entrepreneurs were written about in terms of debates over whether they were “robber barons or industrial statesmen” (i.e. bad or good); and some historians (Morton Keller or Samuel Hays, for example) went further and pioneered studies into the ‘new institutionalism’ that was taking place – however none had actually written about the rise of modern business enterprises, and of the “brand of managerial capitalism that accompanied it”.

The very basic message from his work is that as salaried managers of large multi-unit corporations gained more control over coordinating the flows of good and services within their enterprises (and in doing so, essentially controlling their economy), and as their expansion increased, they began to take the place of small, traditional family firms, which relied on traditional market mechanics as the coordinator of the activities of its economies. As these larger companies then took on a more powerful roles within American economics, it meant that dominant sectors of the economy were actually being controlled by managers – in essence, production and distribution was “concentrated in the hands of a few large enterprises”. In this sense, then, he argues that Adam Smith’s theory of the ‘Invisible Hand’ of the market force had been replaced by a ‘visible hand’ of management. (Considering what Chandler says about how much of the basic economic theory at the times was based on Adam Smith’s model, and the belief that ‘perfect competition’ can only take place between single-units (as opposed to the multi-unit models of the large-scale new enterprises), it can maybe be understood why some contemporary writers considered them “an abberation”, and hadn’t deigned to write much on their history.)

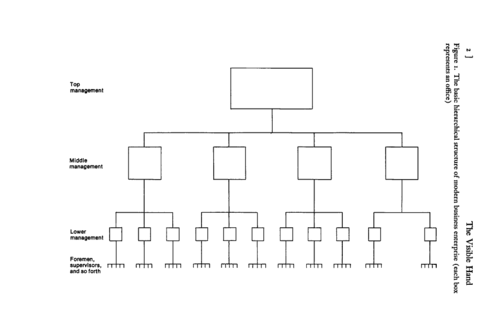

The change between traditional and modern business enterprises happened when many singular units of operation were ‘internalized’, or brought under one umbrella of control. This meant that the activities of the units and the transactions between them were also internalized, and could therefore be monitored. This led to a new ‘class’ of businessmen: middle- and top-salaried managers, who could be charged with monitoring the work of tens or hundreds of thousands of workers in units below him.

Here is a basic idea of how the ‘new’ modern system worked:

Before this becomes too much of a focus on the technicalities of how these business were structure and re-structured, I found that the most interesting part of this text was the way in which Chandler explains the rise in the actual class of person that these managers became a part of.

In basic terms, once the influence of these huge multi-unit enterprises grew and the success of that managerial hierarchy was proved, it became a source of “permanence, power and continued growth”. He quotes Werner Sombart (a German economist and socialist), saying that the modern business enterprise had taken on “a life of its own”. As a result of this, the development of the career-manager came about – the concept of climbing up a professional ladder had a new importance. This meant that there was a fresh sense of professionalism to managerial work: it meant that they developed an approach to their jobs very similar to that of a lawyer, or a doctor, or a minister. He says that this meant that managers, even from different enterprises, carried out similar activities, which in turn meant: they had the same type of training, attended the same types of school, read the same journals and joined the same associations.

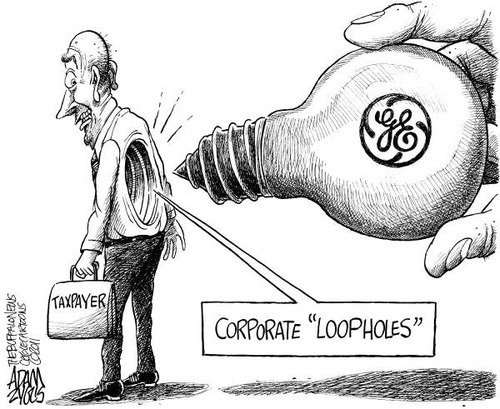

In ‘The Power Elite’ [C. Wright Mills & Alan Wolfe], it is stated the the Power Elite is “composed of men whose positions enable them to transcend ordinary environments of ordinary people”, and are in positions to make decisions that can have enormous consequences; that these sectors with the most influence in terms of power are the political order, the military order and the economy. It also talks about how these people consider themselves ‘inherently worthy’ of the advantages they possess (despite the fact that so often they are in these advantageous positions due to the fact that they are of ‘similar origin and education, careers and styles of life’ and with an ability to “intermingle”). Considering that these ‘modern businesses enterprises’, as Chandler puts it, “altered the basic structure of […] the economy as a whole” due to their influence during the 20th Century, then ‘The Visible Hand’ (despite being an American study), I believe ties in incredibly well with what Alan Milburn (the current chair of the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission) said of the reasons behind the lack of social mobility in the U.K. today:

“One third of MPs, half of senior doctors and over two-thirds of high court judges all hail from the private schools that educate just 7% of our country’s children” – in that it is easy to see how easy it is for elitism to pervade societal system, because when the managers of these ever expanding companies became increasingly from the same class of people, and end up having such an influence on the political sphere as well, is it fair to say that the ‘managerial revolution’ that Chandler speaks of has led to big businesses having a very firm and ‘visible’ hand on how society, as well as just the economy, is run?

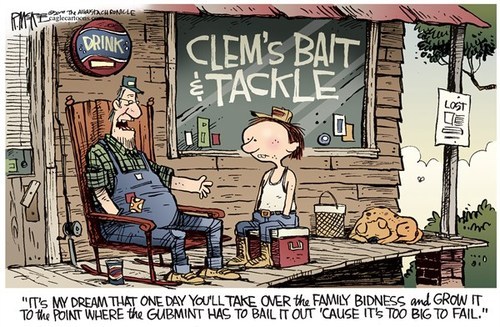

Using this point of view, then, I feel that learning the history of the rise of the business class is very interesting in learning how these elitist classes (in this case, those who own or run enormous companies) have come to exist in the last couple of centuries. It ties in well with what Laura Nader wrote about the importance of “studying up” – it is the only way to begin to understand and help answer questions on the social structure of today. I think the bigger question is whether it really has, as aforementioned, developed a life of its own that is too large to control at all.

Discuss this article